Suez Canal (4 November)

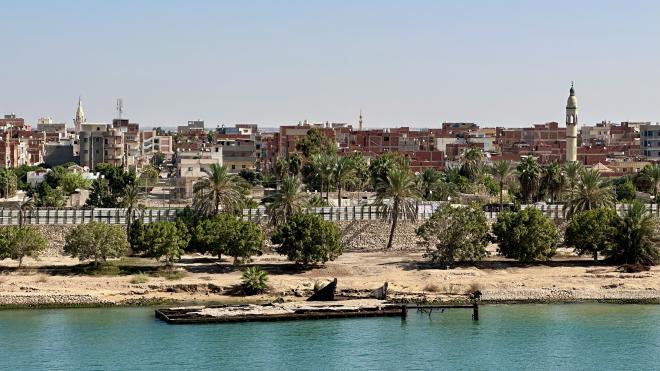

After Heraklion, the next major event on the cruise was transiting the Suez Canal.

The current Canal, dug between 1859 and 1869, is just the most recent of many attempts, going back 4000 years, to connect the Red Sea to the Mediterranean in a way that was useful for shipping.

Unlike the Panama Canal, the Suez traverses relatively flat ground and connects two seas of about equal levels. As a result, it has no locks. This simplified construction of the Canal and speeds transit; however, it has had consequences unforeseen at the time the Canal was planned. Principal among these has been the movement of invasive species in both directions, which has had a particularly detrimental effect on the Mediterranean ecosystem.

Much of the Suez Canal is only wide enough for a single vessel, so traffic has to be tightly controlled. All ships travel in convoys for the transit, normally two southbound and one northbound each day. Each ship has two pilots aboard and is accompanied by tugs. Our convoy formed up in the wee hours of the morning and entered the canal shortly after dawn.

We completed the transit in the evening and began sailing south through the Red Sea towards the Egyptian port of Safaga.